In this audio guide to Franz Kafka’s most important works, Ritchie Robertson of St John’s College, Oxford, who has written an introduction to the Oxford World’s Classics editions of the books as well as A Very Short Introduction to Kafka, discusses Kafka’s life, world and writing. Just click on the links below to listen to the guide.

Part 1: The life

Kafka in Prague

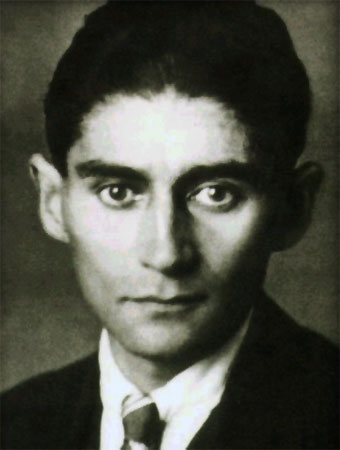

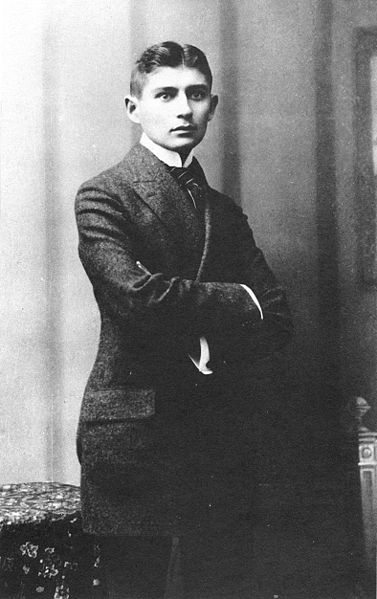

1. Franz Kafka was born in Prague in 1883 to German-speaking Jewish parents who ran a small shop. Ritchie Robertson introduces his milieu here [1:21].

2. Next he discusses Kafka’s legal studies and a civil service career which allowed him time to write. Click here [1:15].

3. Was Prague a thriving cultural centre or a provincial backwater in Kafka’s day? Click here [1:08].

3. Was Prague a thriving cultural centre or a provincial backwater in Kafka’s day? Click here [1:08].

4. Kafka’s professional writings have recently been published in English. Does understanding more about his job shed light on his literary work? Click here [0:46].

intimate relationships

5. Kafka had a famously fraught relationship with his father, Hermann Kafka, captured by the author in his “Letter to His Father”. Here Ritchie Robertson considers Kafka’s relationship with both his parents. I began by asking how much we know about his relationship with Hermann. [2:36].

5. Kafka had a famously fraught relationship with his father, Hermann Kafka, captured by the author in his “Letter to His Father”. Here Ritchie Robertson considers Kafka’s relationship with both his parents. I began by asking how much we know about his relationship with Hermann. [2:36].

6. Kafka’s relationships with women were no less fraught – he was unhappy as a batchelor and unhappy when he was engaged. Click here to discover what kind of women Kafka was attracted to and how women were represented in his fiction [5:35].

Part 2: The works

Kafka the writer

7. Was a full-time literary career ever a realistic option for Kafka? Click here to find out [0:55].

7. Was a full-time literary career ever a realistic option for Kafka? Click here to find out [0:55].

8. What kind of work did Franz Kafka set out to produce and who was he writing for? Click here [1:30].

9. Has the adjective ‘Kafkaesque’ done the writer a disservice by distorting how his literary work is read? Click here [1:01].

10. As he revised his manuscripts, Kafka deliberately made his texts more opaque, removing clues to their possible meaning. Ritchie Robertson reflects on this with particular reference to The Trial here [3:02].

11. Sigmund Freud was a contemporary of Franz Kafka and a fellow-citizen of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Click here for more on Kafka’s attitude to psychoanalysis, education, and the family [4:25].

12. Kafka was perpetually dissatisfied with his work and all three of his novels are unfinished in different ways. Click here to find out more [2:53].

The metamorphosis

13. The Metamorphosis is often the first work by Kafka that newcomers encounter. What kind of reading experience are they in for? Click here [2:37].

14. Kafka’s language and imagery seem marked by a strong sense of the physical and corporeal world. I asked Ritchie Robertson if he agreed with this assessment. Click here [1:11].

15. What were Kafka’s feelings about religion? Click here to find out [2:11].

The Trial

16. What kind of world is the reader of The Trial plunged into? Click here [0:58].

17. Ritchie Robertson describes the world which Josef K inhabits as “a world of an opaque and oppressive legal system but which has very, very strong metaphorical overtones”. What kind of interpretation does the novel invite? Click here [1:47].

18. The reader’s understanding of the world of The Trial can be enhanced by some knowledge of how the Austro-Hungarian legal system viewed the concept of guilt. Click here for Ritchie Robertson’s explanation [2:14].

The Castle

19. Although there are points of comparison with The Trial, The Castle also exhibits salient differences. Ritchie Robertson discusses them here [3:18].

20. Ritchie Robertson sees authority and the possibility of the individual’s resistance to authority as central to understanding Kafka’s work. In a sense, The Castle is a second attempt to answer the question posed by The Trial. He discusses this idea here [0:57].

21. Newcomers with a sense of what ‘Kafkaesque’ means may be surprised to find that Kafka is also capable of humour. Ritchie Robertson discusses the nature of that humour here [2:28].

Part 3: Contexts

texts and translations

22. Here Ritchie Robertson tells the story of Max Brod, Kafka’s close friend, literary executor, and therefore guardian of the author’s manuscripts after his death in 1924. But for Brod, Kafka’s manuscripts might have been lost at the outbreak of the Second World War [0:47].

23. I asked Ritchie next if encountering Kafka’s handwritten manuscripts gave him a frisson that other writers’ works did not. Hear what he said here [0:58].

24. What are the challenges of translating Kafka’s prose into English? Click here to find out [1:56].

beyond the texts

25. For Ritchie Robertson, Kafka’s continuing popularity and the mountain of scholarship he has inspired is due to his status as a classic – inexhaustible and capable of being interpreted anew by each successive generation and critical movement. Click here [2:15].

25. For Ritchie Robertson, Kafka’s continuing popularity and the mountain of scholarship he has inspired is due to his status as a classic – inexhaustible and capable of being interpreted anew by each successive generation and critical movement. Click here [2:15].

26. Finally, Ritchie Robertson suggests that readers start with Kafka’s works themselves and then move on to some of the other books he recommends. He picks some of his favourites here [1:12].