This is a lightly edited transcript of my recent interview with Tessa Laird, which you can find here:

Tessa Laird, who teaches at the Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne, began painting bats as a student after encountering the bats of Australia, which has a much richer variety of them than her native New Zealand. Other bat-related projects followed, the latest of which is a book entitled Bat in the Animal series published by Reaktion Books.

As with all the volumes in this series the reader learns not only about the natural history of the animals but also about humans’ relationship with them across a wide variety of historical and cultural contexts.

In China the bat’s name is a homophone for luck, so it’s often depicted as a symbol of good fortune. But bats, it’s fair to say, have had a pretty bad press throughout much of human history, associated as they are with night, stealth, unpredictability, madness, disease and of course vampirism. As you’ll hear, the situation may now be changing as images of cuddly baby bats proliferate on social media. But for some endangered species it’s too little, too late.

![]() Tessa writes too about subtler manifestations of bat iconography. Bats occur in art as symbols of identity and indigeneity across the Pacific, for example, and throughout there’s a sense that the bat makes us uncomfortable as an uncanny reminder of ourselves. Tessa quotes one writer who refers to bats as ‘weirdly altered alter egos of humans, the mammalian stalactites to the human stalagmite’ and another finds in the bat an echo, if you’ll pardon the term, of how we are when we are at our most crowded, noisy, and irritating.

Tessa writes too about subtler manifestations of bat iconography. Bats occur in art as symbols of identity and indigeneity across the Pacific, for example, and throughout there’s a sense that the bat makes us uncomfortable as an uncanny reminder of ourselves. Tessa quotes one writer who refers to bats as ‘weirdly altered alter egos of humans, the mammalian stalactites to the human stalagmite’ and another finds in the bat an echo, if you’ll pardon the term, of how we are when we are at our most crowded, noisy, and irritating.

Tessa refers to a feeling of ‘betweenness’ the bat produces in us, so when she spoke to me recently from her home in Melbourne I began by asking her to tell me more about this.

Tessa Laird

I suppose again and again what came up was the idea that the bat ought to fit in the category of birds because it’s a flying thing and clearly not an insect. It’s perhaps closer to the bird but it’s not a bird because it looks much more like a rodent, a small mammal. And the fact that a mammal could have wings, I think, is almost a metaphysical conundrum, because it comes from the same [biological] class as us and we don’t have wings and nothing else in that class has wings and therefore there’s something wrong with it. It shouldn’t be. It’s a sort of evolutionary accident.

I think there’s also something peculiar about the hairlessness and featherlessness of the wings that really revolts people. I’m not sure why, but there’s a sense that if the human form were ever to be winged, all the portrayals across different cultures and throughout history show human forms sprouting wonderful, lustrous, feathery bird wings. I think that’s a bit silly because if we were to sprout wings, being mammals and not having any relationship to birds, we wouldn’t have feathered wings, we’d have leathery, bony wings we could wrap around ourselves.

So I think there’s a sort of a terror and a horror in the bat, partly because there’s something about us that’s similar to it. We can see ourselves in the bat, but we don’t like what we see. In the book, when the photographer Tim Flach turns bats the other way round, they’re very easily anthropomorphised. It’s because they appear to be walking on two legs; because they hang from two legs, if you turn them upside down, they appear to be bipeds. They’re also one of the few mammals with only two breasts, so they have the kind of basic structure of humans. I think it’s very scary when we look at that, but see it with these massive outstretched wings. There’s something really creepy about it.

The Hedgehog & the Fox

In the case of primates, the great apes and monkeys, there’s a lot of similarity between us and them, and the usual feelings they inspire are ones of affection and sympathy and identification. The bat, as you’re saying, is like us in some ways but just different enough to be troubling: the flight, the hairlessness, the fact they come out at night. You also mentioned the fact the bat is constantly changing direction, it’s darting, it’s unpredictable, one minute it’s there then the next minute it’s gone. All those things are unsettling, aren’t they?

Tessa Laird

Definitely and that flittery, fluttery thing is a big part, I think, of what has put bats in the category of madness and mental instability, because they’re seen to be metaphoric for changeable and unsound thoughts.

The Hedgehog & the Fox

And I guess the other thing we have to deal with is the myth that bats are perpetually getting entangled in people’s hair, and the other myth, which I guess is based partly on fact, of the bloodsucking bat. But in fact, as you point out in the book, bloodsucking bats are a tiny, tiny minority of all of the bat species. Can you say a little bit about what part you think those things have played in the mythology and the reaction we have towards bats? I hadn’t really thought about the fact that vampire bats hadn’t been discovered by European civilisation till really comparatively recently, a couple of centuries ago, I guess.

Tessa Laird

So, first of all about the hair thing, it’s funny how many different myths came up when I was researching that involved hair or lack of hair. I think that has to do with the fact that the bat is both hairy and bald at the same time. It’s funny the way the French word for bat is bald mouse [chauve-souris] and you think, that that’s odd because they’re not bald, but the wings I suppose you could say are bald, and they exemplify anxiety both about hairiness and baldness simultaneously and have been used for cures for both conditions.

The whole thing about bats getting tangled in people’s hair, it’s so strange how widespread it is, given that virtually nobody on record has actually had it happen. I quote in the book from Tim Pearson, who’s an Australian bat conservationist, and he said, ‘My God I wish it were that simple,’ because he has to set up elaborate bat traps in order to do his research. He said, if it was that simple I’d just get a few people with long hair to stand outside and they’d catch bats in their hair and I could study them. But it doesn’t actually ever happen. It’s a very strange, groundless folk tale.

I also think idea about blindness and sight is interesting. Another thing that kept coming up in my research is that bats were associated both with blindness and visual acuity – probably for understandable reasons: the bat may bumble about in daylight or it may appear to be a darting erratically, but it’s actually got incredibly tuned senses and can navigate exceptionally well, which I think is partly why in China they were recognised as being an emblem of good vision. So if you ate bats, you would see better.

About the bloodsucking, I can’t lay the entire blame on Bram Stoker but he does seem to have been pivotal in tying together the information that was coming from European explorers in South America and also Darwin, who saw a vampire bat at work on a horse, tying that together with old European vampire myths, which didn’t actually feature bats, but did feature shape-shifting undead people, who had the capacity to turn into other animals, but the bat was never one that was listed.

The explorers said, that bat sucking blood is a bit like the old vampire tales of Europe, the old bloodsucking walking dead. Let’s call them vampire bats. Stoker takes that idea, creates this kind of super-villain, and the rest is history. We from now on forever associate vampires with bats, and bats with bloodsucking, and it’s a very unfortunate, although very powerful and genius manoeuvre on Stoker’s part, because he was really tapping into something and he knew it. But it’s been very unfortunate for bats.

The Hedgehog & the Fox

In Dracula it’s often been pointed out there’s a fear of contamination from the east, something coming in and getting into the bloodstream, and I guess the modern-day correlative of that is fear about infection, seeing bats as a vector for disease. In your book you point out that they often get blamed wrongly or hastily for being the cause of viral infections, for example, Ebola.

Tessa Laird

Yes, absolutely. The last big outbreak of Ebola was almost instantaneously pinpointed on a group of bats, but then it seemed as though the reports couldn’t quite fix on that group of bats, so they said maybe it was these little insect-eaters that the children were playing with or maybe it was the fruit bats that the men were hunting in the village across the way. But none of these were actually in the end proven but unfortunately the headlines went out globally saying bats were the cause. Even now they’re still struggling to pinpoint the exact cause and so bats have already got a bad rap in that case and they do frequently get associated with outbreaks of zoonotic diseases.

It’s a really tricky area because we don’t want reprisal killings and we don’t want people to unfairly associate bats with things that they haven’t been responsible for. But at the same time, we don’t want to ignore the fact that they may be harbouring specific diseases or there may be reservoirs of diseases that humans haven’t been exposed to yet and don’t have any immunity to.

I think one of the important things to remember is that bats do have immunity to a range of things that we don’t. They are actually immunity machines; they live incredibly long for an animal of their size and it seems as though they’re able to fight off infections very well. And so perhaps they do hold some keys to human immunities that we could benefit from. So rather than pointing the finger at bats and saying they’re the source of all evil, it may actually be the opposite; they may be the source of some amazing cures and some amazing prophylactics.

The Hedgehog & the Fox

There are many amazing things in your book, Tessa. I think the most amazing, at the same time rather horrifying, is the X-ray incendiary bat bombs planned in World War Two. It’s so amazing I thought you must have made this up, this cannot be true. It’s like the wildest fringe of sci-fi. Can you explain what it was…

Tessa Laird

Well, apparently it’s all true. I read an autobiography by one of the people involved in this project. It was called Project X-ray. An enterprising dentist called Doc Adams, who fancied himself a bit of a polymath, was aware that Texas had an abundance of bats living in caves. We’re talking in the millions. And he hatched this bizarre idea that if little incendiary devices could be strapped to these bats and they could be dropped over Japan, they would all come down and find a roost in the eaves of Japanese architecture, which famously is very flammable. And Japan would be brought to its knees.

This was his great plan and he had a connection; he knew Eleanor Roosevelt. So he was able to get the President to read his proposal. And apparently the green light was given, the funding was given, and several years were spent trying to perfect this bat bomb. There were a lot of accidents, a lot of bats lost the lives and apparently the whole airstrip was set on fire at one point. The remarkable thing about it was that this was going to go ahead until a different project, the invention of the atom bomb, became viable and as soon as that was given the green light, project X-ray was mothballed and there was no need for it. But it is a crazy story and apparently a true one.

The Hedgehog & the Fox

You’ve got a lovely quote from Doc Adams in the book where he’s basically pouring scorn on the atomic bomb and saying, ‘why they are following this hare-brained plan when we’ve got a sure-fire Bat Bomb in the works?’

Tessa Laird

Exactly. Because they thought, ‘the bat is small enough. Now an atom, that’s ridiculous. How can you make a bomb out of an atom?’ Of course, we all know how it ended – it’s such a sad tale because it ended in such tragedy for the people of Japan. The author of the book says he thought the Bat Bomb would have actually been a more humane option, not for the bats of course, but for the people of Japan. It’s funny to think that if the atom bomb had never got off the ground, maybe the cold war would have been about stockpiling bats, you know, who’s got the biggest stockpile of bats.

The Hedgehog & the Fox

And we wouldn’t have the iconography of the mushroom cloud, we’d have the bat wings hovering…

Tessa Laird

And then bats would have an even worse reputation than they do.

The Hedgehog & the Fox

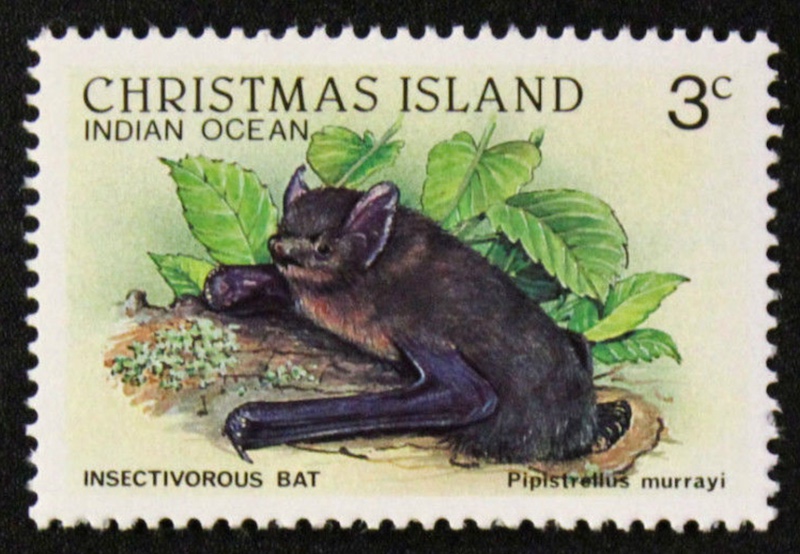

If that’s the most bizarre story in the book, I guess the saddest one is about a species of bat on Christmas Island and that points towards a really serious problem, a more general problem, for bat populations; I think you say 25% of bat populations are threatened. Can you tell me about the Christmas Island bat?

Tessa Laird

The Christmas Island pipistrelle was a bat which became extinct only a few years ago. Christmas Island is an Australian territory and due to the introduction of particular snakes and other predators, a lot of the local fauna was suffering. Conservationists knew that the Christmas Island pipistrelle was struggling and petitioned the Australian government to take action and to allow them to go in and set up some intensive breeding programmes, but funding didn’t come through.

The scientists involved kept pushing for it and pushing for it, and then it was too late. By the time they were given any funding, they got to the island and there were less than a handful left. It got to the point where they were recording the echolocation call of the very last bat of that species. And then it was gone. Its call was archived by Bat Conservation International and you can listen to it on the Internet. They labelled it ‘the sound of extinction’. It was really traumatic for the scientists involved being around something we hear about all the time – we’re in the sixth mass extinction event and many species are going extinct every year – but to actually be faced with the very last of a species, it’s such a difficult and profoundly sad experience. I think there’s a lot to be learned from that, but whether or not we can move do something about all the bats and all the other creatures that are in peril, I don’t know.

The Hedgehog & the Fox

There’s a very poignant picture in the book of little inverted crosses hanging from trees in Australia recording sites where bats have been shot.

Tessa Laird

Yes, it’s surprising, but in Australia a lot of bats aren’t safe, because even though some of them, such as the grey-headed flying fox, are protected species and are recognised as being threatened, they also are fruit-eaters, so fruit farmers see them as pests and can apply for a shooting permit in some states because they’re allowed to protect their crops any way they see fit.

There’s been a lot of work done to show that it’s far more effective to net your fruit correctly rather than shoot randomly as you have to be a very good shot to kill the animal, it’s been proven that often they just get wounded, maimed and then die really a horrible, lingering death. Often they are nursing mothers that are flying with pups attached to them. It’s a horrible, messy business. Bat advocates around Australia are saying there’s no need to shoot flying foxes when there are perfectly ethical, humane ways of protecting fruit trees and bats, flying foxes in particular, already die enough from other causes such as heatwaves, barbed-wire fences, electrocution.

There’s a whole number of perils for flying foxes, so there’s a burgeoning field of bat carers, generally middle-aged women, perhaps after their families have left, who end up nursing orphaned bats whose mothers have been electrocuted, shot or have died in a heatwave. These little baby flying foxes are swaddled and they’re given dummies to suck and they’re fed fruit juice and then they graduate on to big chunks of fruit and they’re extremely beguiling and you can see these videos on YouTube of these little baby bats and I think once people have seen these it’s very hard to not fall in love with bats and to continue to see them as kind of evil or creepy. You really start to see their endearing qualities up close.

The Hedgehog & the Fox

I wanted to ask you about that. We talked about the demonic depictions of bats that have prevailed in Western society for centuries, but do you actually think things like social media are making a significant difference to how bats are perceived? If they’re not hanging in some dripping cave, but you can see them swaddled and eating fruit, that does begin to change people’s image, doesn’t it?

Tessa Laird

I think so. I’m the least social media person there is, but I really do think the perception of bats is changing thanks to the bat baby videos and the kinds of things that are posted on Facebook. They’re starting to be seen as cute, endearing and fun. For example, a while back there was a video again of that idea of flipping the bats upside down [photographically] and there were horseshow bats hanging upside down (when I say upside down I mean the right way up [for humans].) They inverted the way the bats naturally hang, so it looked like they were standing upright and doing a little dance. And, of course, that was shared throughout social media and people said, ‘aren’t they cute?’ That kind of thing does help. There’s also been a lot of education aimed at kids, so kids are getting the idea that bats are really good for the environment and not to be feared and perhaps they can then influence their parents a little bit more.

I also think that even though in general the spread of American culture is the scourge of the earth, the fact that Hallowe’en has now become a cool thing to do even outside of America means that imagery of bats looking cute is changing the way we perceive the animal, which I think is a positive.

The Hedgehog & the Fox

It’s just a question of whether there is enough time to effect genuine change and of course it’s not an isolated problem, it’s one of an interconnected suite of problems about environment and lifestyle.

Tessa Laird

That is true. And in that sense, as much as I love Bat Conservation International, I feel that by focusing on bats only, we often lose sight of some of the bigger problems, things like climate change and the loss of habitat and these things really need a holistic approach.

The Hedgehog & the Fox

Let us conclude, Tessa, with what sounds to me like an astonishing experience you had while researching the book, visiting Bracken Cave in Texas. It sounds like the full awe and majesty of the bat world before your eyes! Can you tell me what that experience was like?

Tessa Laird

It’s overwhelming, because you hear about it and you hear about the endless stream of bats and you hear about how many there are and there are literally millions. I’ve heard twenty million. I’ve even heard forty million. And when you get there, you see that this cave actually looks very small. The mouth of the cave is not big and you think, OK, well, there can’t be that many bats in there. But they’re very little bats. There’s something strange about when you see that many of them. It’s almost hallucinatory and you can’t quite put your finger on what you’re seeing because they start to form patterns and I kept thinking, it’s like insects and then I kept thinking, no, it’s like birds and thinking, it’s like waves on sand and then it would turn into something else, it keeps morphing and shifting and all that time you think, God, it’s still going and it’s still going, it’s still going. It’s really a wonderful experience.

I feel so lucky to have seen it and I think about those great migrations that used to exist, such as the buffalo and the passenger pigeon. The great migrations that used to be great sight to behold that no longer happen because the passenger pigeon was shot to extinction and there are no great buffalo herds of the size that there used to be, so you don’t get that incredible stampede.

And I think even the monarchs are in trouble, the monarchs that plaster everything in Mexico with orange and black in a certain season. I feel that these epic sights are on the wane and I was so lucky to have seen Bracken Cave when I did and I just really, really hope that it continues to be healthy. Bat Conservation International have bought the land and are doing a wonderful job of keeping developers out of the area. One can only hope that it continues for a long time to come.