This week we’re focusing on one of the nineteenth century’s most successful and influential writers, Victor Hugo. By the time of his death in 1885, Hugo was undoubtedly the most famous French writer in the world, a literary colossus who had made his mark in the theatre, as a novelist and poet, and as a statesman. An estimated two million people lined the streets of Paris for his funeral.

Hugo wrote Les Misérables on Guernsey during his long political exile from France’s second empire; that sprawling book has been called ‘the novel of the century’. It was an international bestseller and exemplified Hugo’s belief in literature’s power to bring about change. Even today, its power to inspire new incarnations shows no sign of abating; witness the recent BBC dramatization, for example.

Some, though, find Hugo too much. When the poet Charles Baudelaire described Hugo’s natural domain as ‘the excessive, the immense’, he meant it positively, but it’s possible to feel overwhelmed by that excess and immensity. Hugo’s complete works run to forty-five volumes, after all.

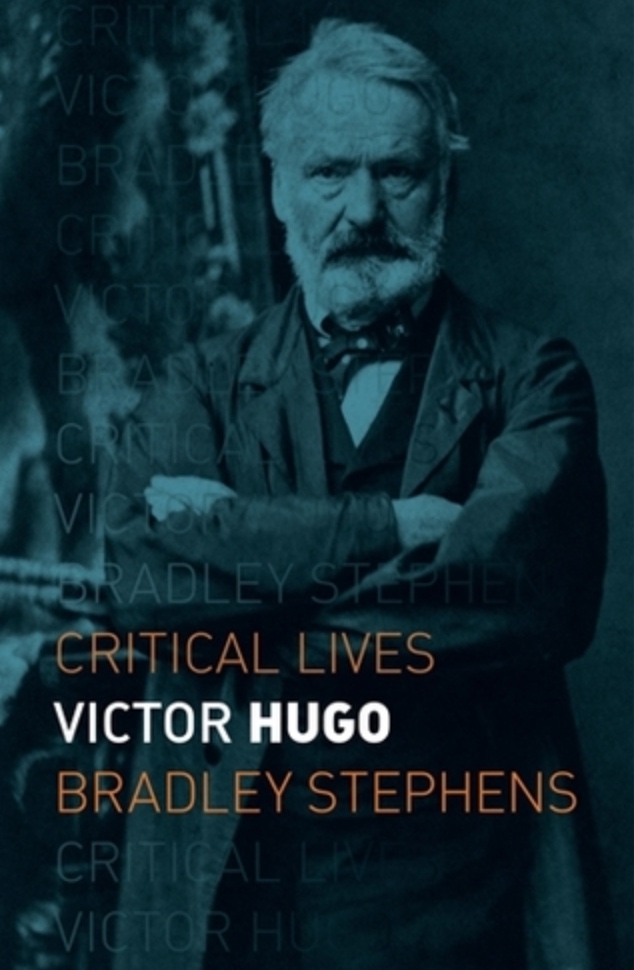

Hugo has found an eloquent new champion in my guest on this programme, though; Bradley Stephens of Bristol University has just brought out a new biography of Hugo, the first in English in over 20 years.

He writes:

‘Victor Hugo’s life can read like an epic novel. Born in 1802 and dying in 1885, he bore witness to the aspirations and anxieties of a century that continues to speak to our own […]

‘My biography of Hugo offers a concise but full account of his artistry and activism in the light of what was, by any measure, a momentous life. […]

‘A figure comes to light that is more modest and apprehensive than a victorious and self-obsessed demigod.’

Returning to Baudelaire’s 1861 essay: he said that Germany had Goethe and England had Shakespeare and Byron, so perhaps France was legitimately due Victor Hugo. I began my conversation with Bradley by asking him about Hugo’s status in France today.