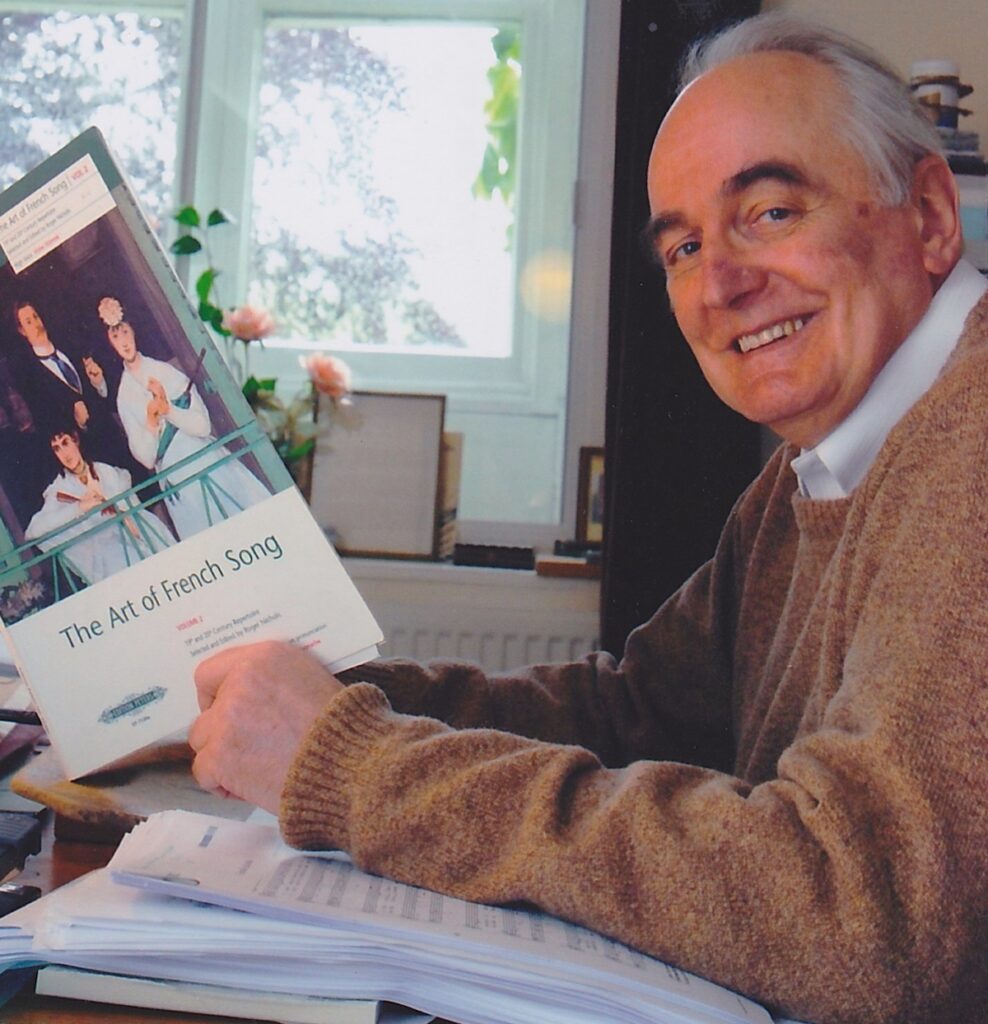

In this programme, we’re exploring the life and music of Francis Poulenc, in the company of writer and musicologist Roger Nichols. Yale University Press recently published Roger’s biography of the French composer, who was the pre-eminent figure in the group of musicians known as Les Six and remains its most-performed and best-loved member.

The best part of 40 years ago now, it was Roger Nichols’ broadcasts on Radio Three that really opened my ears to French music. Until then, I’d been in the thrall of the German tradition, but he played a major part in introducing me to the scintillating textures of Ravel, the wit of Chabrier, and the bittersweet melodies of Poulenc. In time, I confess I left Poulenc behind. Too slick, too glib, I reckoned, the bittersweet too close to the sentimental.

I was wrong, of course, but it took Roger’s new life of Poulenc to show me that, to send me back to listen again to works I thought I already knew and on to works I’d never heard before.

The songs, I hardly knew, and they are rich, deep and astonishing – and he set some of my favourite French poets, Guillaume Apollinaire and Paul Eluard. The religious and choral music, I hardly knew, and it too can reach depths I hadn’t associated with the composer.

If you feel you have Poulenc’s measure, seek out his setting of four short poems by Eluard, Un Soir de neige (A Snowy Evening) and see if it changes your mind. ‘La nuit le froid la solitude’ – cold, dark and lonely is not an atmosphere we associate with Poulenc.

Of course, Poulenc sometimes is sentimental, deliberately, unashamedly, and he once declared: ‘A vulgar tune is good if it works’. But there’s nearly always an irony to cut through sentiment. What he abhorred, as Roger’s book shows, was emphase, a sort of self-important grandiloquence, a sort of Wagnerism.

But perhaps what Roger’s biography taught me is that in certain lights, limpid waters may appear shallow, but in fact contain depths. After all, Poulenc was not an uncomplicated man – he had bouts of depression and self-questioning and a love life that he kept very private, sealed off from his musical friends.

In the interview, we talk about the character and range of Poulenc’s work and I ask Roger if Poulenc’s verdict on his compatriot Gabriel Fauré might equally well apply to Poulenc himself: ‘a minor master’?