In this episode, I’m talking to Juliana Adelman, who’s assistant professor of history at Dublin City University. Juliana’s recent book, Civilised by Beasts: Animals and Urban Change in Nineteenth-Century Dublin, may sound like it’s quite narrowly focused – one aspect of one city in one century. But that would be to ignore how omnipresent animals were in cities, even into the twentieth century; how cities depended on animals to function – horses literally turned the wheels that kept transport and commerce going. And animal husbandry was much more visible in cities then than now, whether that was cattle being herded to market or to slaughter, or pigs being kept in back alleys, literally cheek by jowl with the human residents.

Juliana vividly conveys the human-animal coexistence in Dublin: anyone standing in the main thoroughfare of Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) around 1820 would know, she writes,

one street to the west lay a warren of butcher shambles crowded with cattle, and even passengers in an elegant carriage could catch the scent of bone boilers and piggeries on the breeze.

Paying attention to the animals and what people say about them is a very good way of registering change in a city. Change in its material life, how it operates, and also change in attitudes. As Juliana writes:

Ideas about animals in particular shaped reform movements in the city, altered its social and economic geography and affected the daily lives of its human and animal inhabitants. This book examines these ideas about animals, and how they changed, in Dublin between 1830 and 1900.

Animals feature in sometimes surprising ways in the context of Ireland’s social, political and religious divisions: not just to debates over the zoological gardens and their perceived civilising effect, but also in the Great Famine, when the composition of people’s diets came under scrutiny.

One long-term trend is the middle classes became increasingly concerned with urban improvement, which entailed asserting greater control over animals and those who looked after them: which animals where permitted where and when in the city, and what it was lawful to do with them. Unsurprisingly perhaps, it’s a story of animals and associated trades being inexorably pushed to the margins.

When we spoke towards the end of last year, I began by asking Juliana about capturing the texture of daily life in nineteenth-century Dublin.

You can listen to the episode here:

Apple: https://apple.co/2Q7Gsh5

Google: https://bit.ly/3fV5jPT

Spotify: https://spoti.fi/3mwFoze

The book is currently available as an ebook and in hardback, but you can pre-order the much more affordable paperback edition now to receive a copy in October 2021.

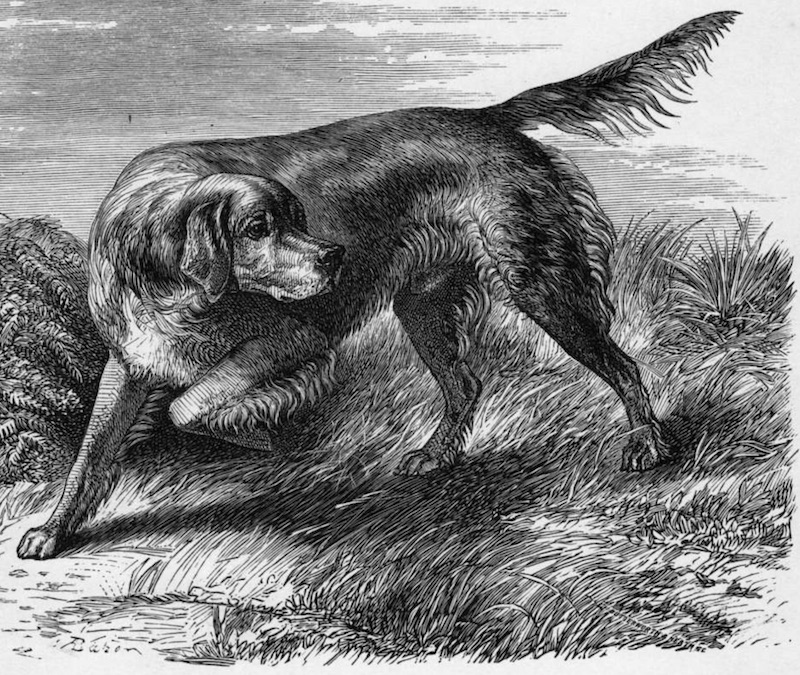

Extract: Dog shows and Irish setters

Dog shows permanently altered the appearance of Irish dogs. For example, Irish dog breeders rapidly eliminated colour variety among setters. By 1866, patches of white or black were out of fashion. Harry Blake Knox, a breeder resident in one of Dublin’s south-eastern suburbs, argued that the proper colour for an Irish setter was ‘blood- red’; white should be excluded or at least limited to ‘the centre of the forehead and the centre of the breast’.

Black streaks were unacceptable and eye, nose and whisker colour was limited. Red colour assured purchasers of ‘pure’ breeding. When Knox’s male red setter impregnated a black-and-tan setter bitch, the resulting puppies showed black streaks and Knox ‘of course, drowned them’.

This new standard departed from that of the past, a historian of the breed noted:

‘The sportsmen of one hundred years since were evidently not very particular about the dogs as long as they did their work well, but since the days of dog shows, breeders have been breeding their dogs free from white.’

By the twentieth century almost all Irish setters were dark red. Prizes at the dog shows were awarded for red setters so breeders abandoned the red and white variety. This variety was ‘indeed not quite extinct, but being less popular than the other, is eliminated.’

Juliana Adelman, Civilised by Beasts: Animals and Urban Change in Nineteenth-Century Dublin (Manchester University Press, 2020)