“In Russian music you have a very different portrayal of Russia [from the one you find in literature], which has very strong rhythms, very festive images. It’s very bright, very colourful, very, very different from the ‘melancholy Russian soul’.”

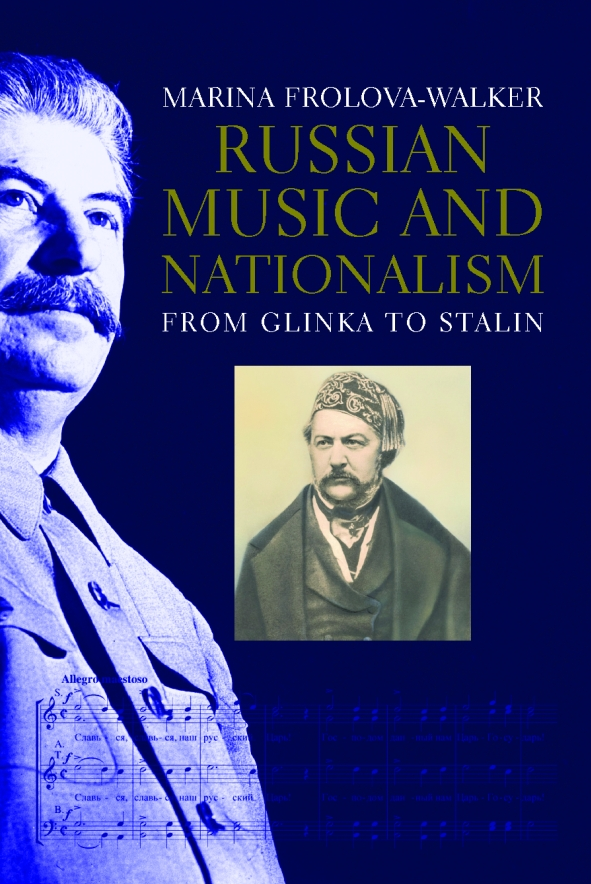

This week’s programme comes from the archive as I haven’t quite emerged from a bout of flu. It’s an interview I did with Marina Frolova-Walker in Cambridge in 2008, shortly after the publication of her book Russian Music and Nationalism from Glinka to Stalin. Here’s what I wrote about it at the time:

Writing of Glinka’s opera A Life for the Tsar after its premiere in 1836, one Russian critic boldly predicted that ‘Europe will be amazed’. Surely Europeans would now want to ‘take advantage of the new ideas developed by our maestro’? Yet this opera, which is regarded as the very foundation of Russian music in its home country, is little known abroad, its composer (the ‘great father of Russian music’) merely another name in the long list of half-neglected nineteenth-century Russian composers.

Writing of Glinka’s opera A Life for the Tsar after its premiere in 1836, one Russian critic boldly predicted that ‘Europe will be amazed’. Surely Europeans would now want to ‘take advantage of the new ideas developed by our maestro’? Yet this opera, which is regarded as the very foundation of Russian music in its home country, is little known abroad, its composer (the ‘great father of Russian music’) merely another name in the long list of half-neglected nineteenth-century Russian composers.

Marina Frolova-Walker, a Russian-born musicologist now based in Cambridge, set out to do something much more ambitious than explain the neglect of certain Russian composers. She wanted to examine the whole notion of ‘Russianness’ in Russian music, a story which starts with Glinka. What did Russianness consist of? How did it come about? What changing ideological purposes did it serve?

This last question becomes especially acute when she leaves the nineteenth century behind for the more politically dangerous waters of the twentieth. In the era of Stalin, writing the wrong sort of music could have dire consequences, so the issue of what was appropriately Russian music for the Soviet Republic was not an academic one. Music was also a key ingredient in providing an escape valve for nationalist feelings in Russia’s Asian republics without them boiling over into serious dissent. The book, Russian Music and Nationalism from Glinka to Stalin, is a fascinating exploration of a topic which is little examined in the west.

If this interview is of interest, do check out Marina’s most recent book, Stalin’s Music Prize: Soviet Culture and Politics, published last year by Yale. She has described it as her magnum opus.